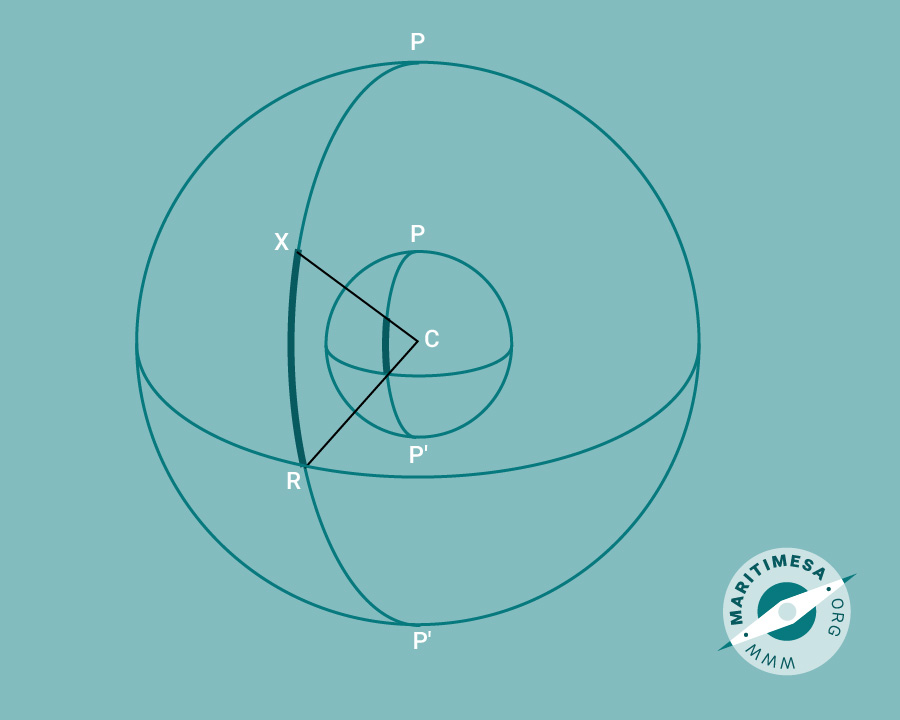

Polar Distance.

This is the angular distance of a body from the elevated pole (the pole that is above the celestial horizon). This is the distance PX in the sketch. When the elevated pole and the declination have the same names, the polar distance is 90° – declination. When they have different names it is 90° + declination.

Polar distance and geographical position.

Geographical position.

If a line drawn from a heavenly body to the earth’s centre, the point where this line cuts the earth’s surface is called the geographical position of the body, ie XC. The geographical position of a celestial body is very important to the navigator when using celestial bodies for navigation.

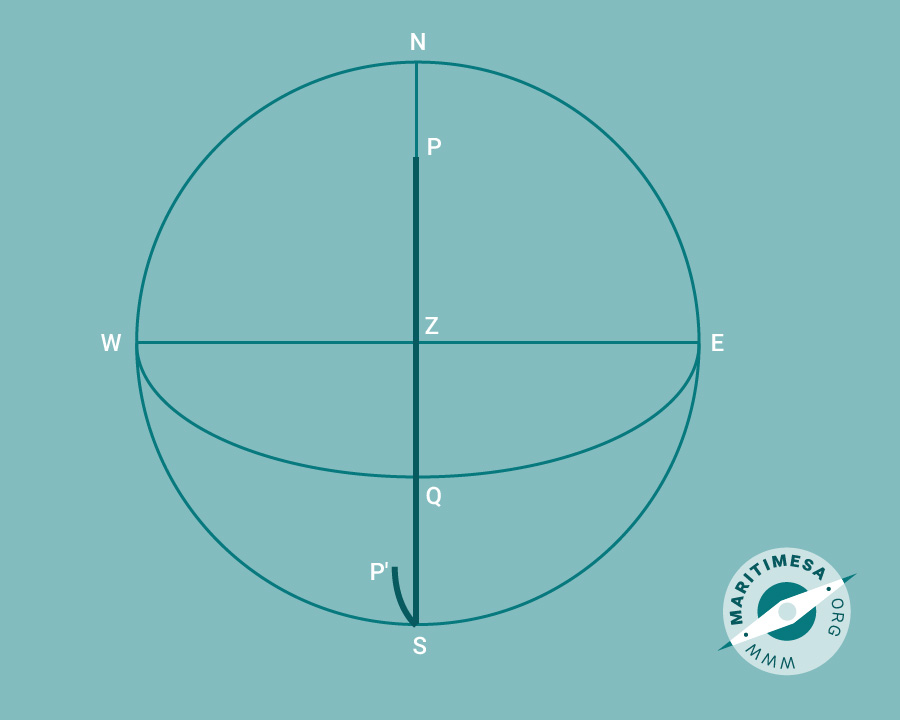

The Observer’s Zenith.

This is the point where a straight line from the earth’s centre passes through the observer’s position and cuts the celestial sphere. When drawing a sketch on the plane of the celestial horizon,it is the centre of the circle marked with the letter “Z”.

The observer’s zenith.

The celestial or rational horizon.

The great circle formed by the celestial sphere, every point of which is 90° from the observer’s zenith, is known as the celestial or rational horizon. It divides the sphere into two hemispheres, the upper one being the visible hemisphere.

The Observer’s Meridian.

This is the celestial meridian which passes through the observer’s zenith from one celestial pole to the other, ie PZQSP’. The points N and S, in which the two meridians cut the celestial horizon are the north and south points, the north point being the one nearest the north pole. The east and west points (E and W) lie on the celestial horizon midway between N and S.

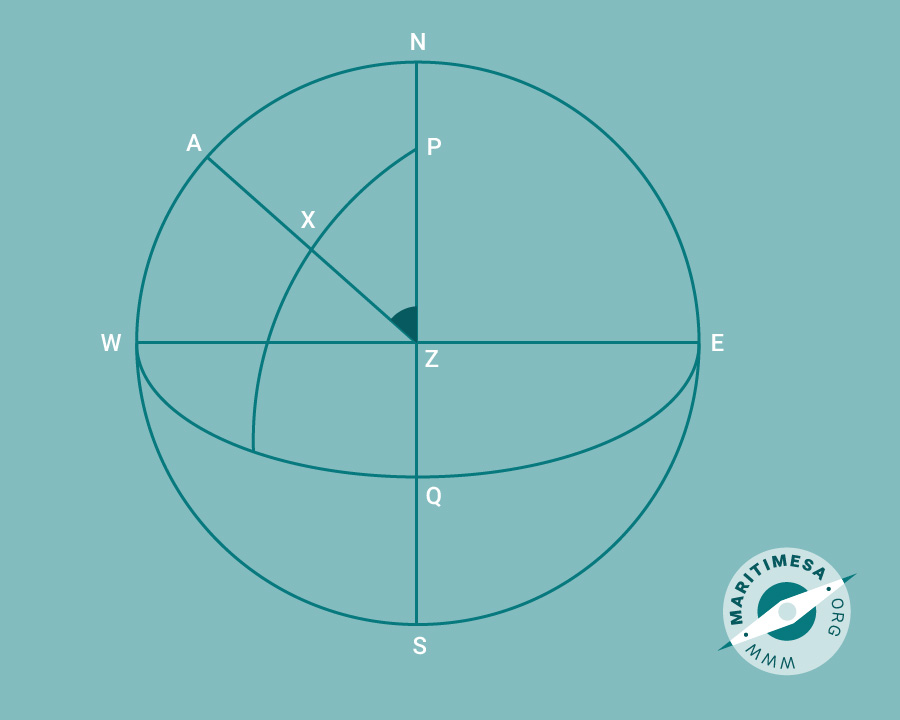

Plane of the celestial horizon.

When it is necessary to show the whole of the visible sky, the figure must be drawn on the plane of the celestial horizon, as if the sphere were seen from a position directly above the observer’s zenith. The zenith (Z)is therefore in the centre of the circle that is the celestial horizon, the north-south and east-west lines divide the circle into four parts and the equator appears as a curve stretching from W to E through the point Q on the N-S line. ZQ is the observer’s latitude, P is the elevated pole.

PZ + PN = 90° = PZ + PQ

therefore PN = ZQ

Sketch of the plane of the celestial (rational) horizon.

Vertical Circles.

All great circles passing through the observer’s zenith are perpendicular to the celestial horizon and are known as vertical circles.

Prime Vertical.

The particular vertical circle passing through the east and west points is called the prime vertical circle. In the above sketch this will be line WZE.

Principal Vertical Circle.

The observer’s meridian is sometimes called the principal vertical circle because it provides a fixed direction in the celestial sphere just as the observer’s terrestrial meridian provides one on the earth’s surface. In the above sketch this is line NPZQS.

The Azimuth of a Heavenly Body.

This is the angle at the zenith between the observer’s meridian and the vertical circle through the heavenly body and it is measured east or west from this meridian from 0° to 180° and named north or south from the elevated pole. The azimuth is not always the same as a true bearing since the latter is measured from 0° to 360°. The azimuth can never be greater than 180°. In the above sketch it is the angle PZX.

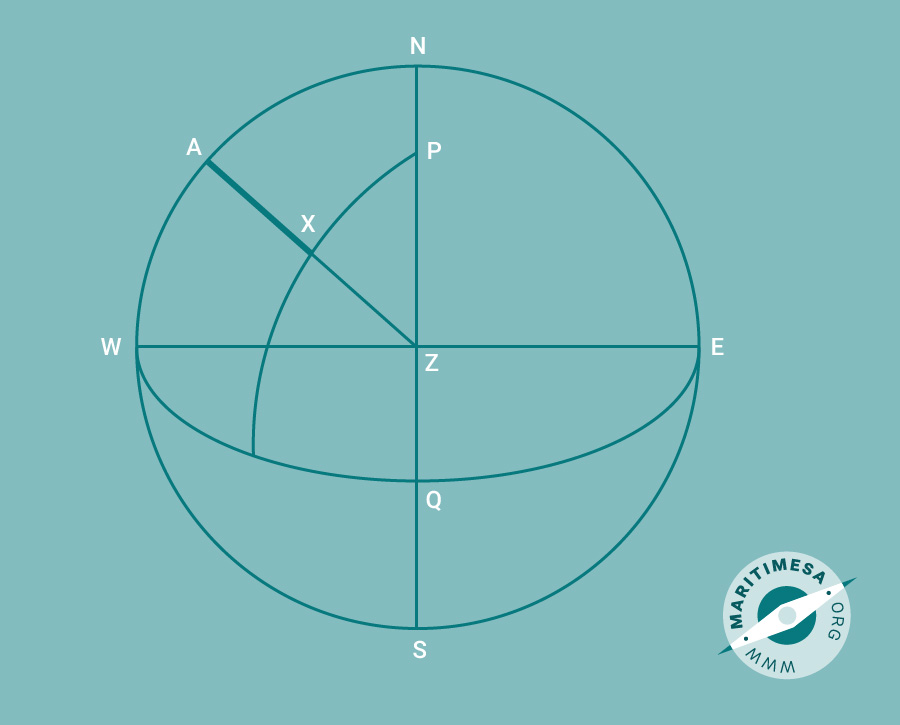

Altitude.

Although the position of a heavenly body is fixed in the celestial sphere, in order for an observer to point out a heavenly body, he utilizes his own meridian and the visible horizon. He will use a bearing from his own meridian (azimuth) and an altitude of the body above the horizon. He will also make use of these to find his own position. As a result, he is not only interested in the altitude of the body above the visible horizon but also the altitude above the celestial horizon. Having measured the one, he will apply certain corrections until it refers to the other.

The True Altitude of a Heavenly Body.

This is the angular distance of the body above the celestial horizon, measured along the vertical circle through the body and the observer’s zenith. The true altitude of X is AX in the sketch below:

The true altitude of a heavenly body.

Zenith Distance.

Once the true altitude of a celestial body is obtained, the distance of the body from the observer’s zenith can be found, ie ZX. It is (ZA – XA) or (90° – altitude). The distance ZX is known as the zenith distance and it is important because it is the third side of the spherical triangle PZX.

True Altitude of the Pole.

The true altitude of the pole is the latitude of the place from which the observation was made.

The Observer’s Sea or Visible Horizon.

This is the horizon above which the observer actually measures the altitude of the heavenly body. It is a small circle drawn around the observer where the sea and sky appear to meet. A tangent from the observer to the earth’s surface decides the position of this circle, but refraction alters it slightly because a ray of light from the horizon is not a straight line.