Vertical and horizontal movement.

Wind can be defined as the movement of air from a high pressure to a low pressure area. Consider two columns of air AB and CD. They are of equal cross sectional area, height and temperature and the pressure at A and C are equal and that at B and D also. If AB is warmed, it will expand to AE, if the area remains constant. Although the pressure at A will remain unaltered, the pressure at B will increase relative to that at D. To equalise the pressure, air will flow from B to D. This will cause a drop of pressure at A and a rise at C. This will cause air to flow from C to A. This illustrates the vertical circulation of air. The rate of flow will depend on the pressure gradient between C and A.

Vertical and horizontal movement of wind.

Geostrophic force.

The movement of air straight from a high pressure to a low pressure only occurs either very close to the equator or in places where the high and low pressure areas are small and the centres are very close to each other. Elsewhere, due to the rotation of the earth, there is a deflective force which prevents air flowing directly from a high pressure to a low. This force is called the geostrophic or cariolus force. In the northern hemisphere the wind is deflected to the right and therefore tends to follow a clockwise direction around a high pressure system away from the high’s centre. In the southern hemisphere it is deflected to the left and follows an anti-clockwise direction from the centre.

Wind changing direction.

When the direction of the wind changes in a clockwise direction, ie from south-west to west, it is said to veer. When it changes in an anti-clockwise direction, ie from south west to south, it is said to back.

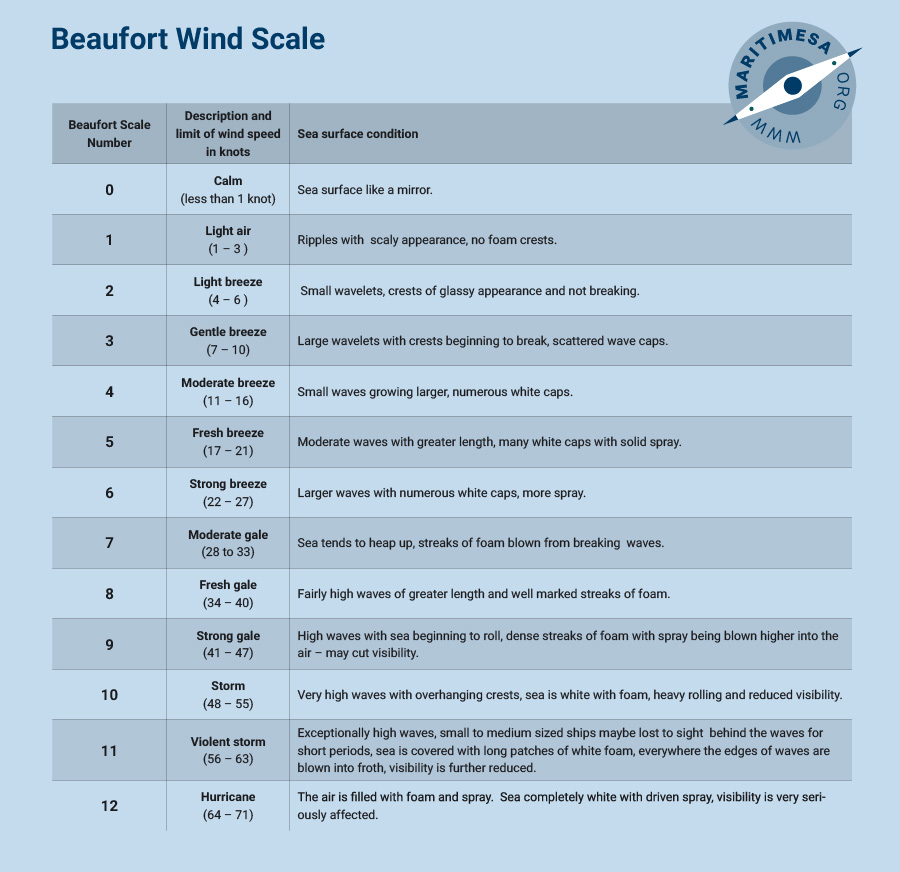

Wind strength and the Beaufort scale.

Wind strength can be assessed by observing the surface of the sea. A special scale was developed to facilitate this, called the Beaufort scale. On the bridge of a ship you will find a copy of the Beaufort scale inside the cover of the ship’s log book.

Beaufort scale (full name – the Beaufort wind force scale).

Prevailing winds.

The Baillie Rose. On climatological charts the frequency, direction and strength of wind are depicted by a wind (Baillie) rose. The following figure is an example of such a rose:

Baillie rose.

From the circumference of the circle to the inner end of the wind arrow represents a scale of 5%. A thin line represents wind force of 1 to 3, a double line represents a wind force of 4 to 7 and a broad line forces of force 8 and above. The centre of the figure shows the number of observations, the percentage frequency of variables and the percentage of calms, in that order.

The wind arrow.

On weather maps, wind is depicted by an arrow having feathers. The direction of the wind is indicated by the direction in which the arrow is pointing. The speed is depicted by the number of feathers, ie each feather equals 10 knots, a half feather equals 5 knots.

Wind arrow indicating wind from the east with a wind speed of 40 knots.

Land and sea breezes.

Sea breeze. As the land is heated during the daytime, the air over it will be heated by conduction. This heating causes a decrease in the density of the air and the atmospheric pressure falls. The sea temperature remains more or less the same and the pressure over it is high compared with that over the land. The pressure gradient is sufficient for air to flow from over the sea to the land and a sea breeze results. The sea breeze sets in during the morning, reaches its maximum at around 1400 and then dies away towards sunset.

Land breeze. After sunset the land cools rapidly and the air above it also cools and its density increases, giving rise to an increase in atmospheric pressure. The pressure over the sea is now low compared with that over the land. The pressure gradient causes air to flow from the land to the sea, resulting in a land breeze. The land breeze sets in shortly after sunset and continues to dawn.