Directly or indirectly, a single voyage by a ship can involve numerous countries, as shown by the list below :

- The ship is registered in Panama.

- She has German officers and Filipino crewmembers.

- She is managed by a management company based in Hong Kong.

- She is insured through British marine insurers.

- She is classed by the Norwegian classification society.

- She is on charter to a Chinese company to carry South African coal to China.

- She will pass through the territorial waters of South Africa, Mauritius, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan and China.

This voyage will involve 14 countries, but another voyage could involve even more countries. Imagine a Danish-flagged containership carrying about 8000 containers in which cargo comes from 15 different countries and heading for 10 other countries, and on a voyage from Germany to China, she will pass through the territorial waters of about 18 countries!

To ensure uniformity of all legal aspects that cold arise during the voyage, it is essential that the maritime laws of each country conform to a common legal base. To create this common legal base for all maritime activities, the United Nations established an agency (International Maritime Organisation – IMO) based in London. The IMO passes regulations (known as codes or conventions) that cover many aspects of maritime operations. Each member state of the IMO must ensure that its own legal system includes all the IMO regulations and proper systems to ensure that ships and shipping companies adhere to all the regulations.

To enforce the IMO regulations, each IMO member state must establish a control system for its own ships and for other countries’ ships as they pass through its territorial waters and call at its ports. The control system will involve the following :

Port State Control

In South Africa, the Port State Control Authority is known as the South African Maritime Safety Authority (SAMSA). In the USA, the Port State Control Authority is known as the US Coast Guard, and in Britain that authority is known as the Maritime Coastal Agency. The role of Port State Control varies from country to country but usually includes the following functions:

- Conduct surveys of ships calling in ports to check their seaworthiness, the management of the ships, the crewing of the ships, and their compliance with other IMO regulations;

- Control the movements of ships within the country’s territorial waters via the automatic ship identification systems and satellite or other surveillance systems. Ships not conforming to local regulations can be ordered into port or to leave the country’s territorial waters. In some extreme cases, Port State Control can order a disabled ship to take a tow from a designated tug.

- Supervise towage or salvage operations within the country’s territorial waters;

- Conduct inquiries into accidents within the territorial waters of that country.

Flag State Control (See 2.1. Registration of Ships above)

South African Maritime Safety Authority

This is the organisation that acts as the Port State Control and Flag State Control in South Africa. Its headquarters are in Pretoria and there are offices in all the ports. The port offices are headed by an official known as the Principal Officer (usually a qualified master mariner), and ship surveyors (qualified navigating officers or engineering officers) do the port state or flag state surveys of ships. The offices in Durban and Cape Town also monitor maritime training institutions in respect of their syllabus, level of instruction, qualifications of teaching staff, moderation of examinations, and conducting of oral examinations for certificates of competency (e.g. second mate’s certificate, chief engineer’s certificate, master’s certificate, etc. )

Some IMO Codes/Conventions

Safety of Life at Sea Convention (SOLAS) The main objective of the SOLAS Convention is to specify minimum standards for the construction, equipment and operation of ships, compatible with their safety. Flag States are responsible for ensuring that ships under their flag comply with its requirements, Among the aspects covered by the SOLAS Convention are the following

- The subdivision of passenger ships into watertight compartments so that after damage to its hull, a vessel will remain afloat and stable. This was particularly important after it was found that one of the reason for Titanic sinking was that her watertight compartments did not reach to the main deck, a factor that allowed water to flow over successive bulkheads as they were submerged in the sinking ship;

- Fire safety provisions for all ships with detailed measures for passenger ships, cargo ships and tankers. This includes the frequency of fire drills.

- Life-saving equipment and arrangements, including the requirements for lifeboats, rescue boats, liferings, liferafts and life jackets, as well as the frequency of lifeboat drills and other life-saving drills. This also covers the procedures that have to be followed when crewmembers enter confined spaces;

- The compulsory carriage of radio equipment (the Global Maritime Distress Safety System -GMDSS), Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) and Search and Rescue Transponders (SARTs);

- Proper manning of ships by mariners who have qualifications in safety measures at sea, and in emergency response measures;

- Requirements for the stowage and securing of all types of cargo and containers, including the carriage of dangerous goods in compliance with the IMO’s International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code;

- Specifications for the structure of bulk carriers over 150 metres in length.

Marine Anti-pollution Convention (Marpol) governs measures and procedures that ships need to introduce to avoid pollution involving the disposal of waste matter (including sewage, galley waste), the level of cleanliness of water that is to be disposed of at sea, and procedures that are to be taken in the event of an oil pollution incident. It also covers the design of tankers to prevent oil pollution, the requirements to regulate air pollution emitted by ships, including the emission of ozone-depleting substances. It prescribes the use of “scrubbers” in ships’ exhaust systems to reduce the amount of sulphur and nitrous acids in ships’ exhaust gases.

Standards for Training and Certification of Watchkeepers (STCW 95/2010) This convention was initiated several years ago and amended in 1995 and again in 2010. (See 1.3. International Employment of Seafarers above.)

International Safety Management Convention (ISM) provides an international standard for the safe management and operation of ships and for pollution prevention. The Code was introduced after the loss of the ferry Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987. The subsequent inquiry detailed that the fault for the loss of the ship did not only lie with some of those aboard, but also some of the shoreside management who ignored complaints or other information given to them about the operation of these ships.

The code overlaps a little with other IMO Codes and Conventions, but goes a bit further in respect of the following areas:

- Ensuring safe practices on ships;

- Preventing human injury or loss of life;

- Avoiding damage to the environment and to the ship;

- Every ship having a safety management system to which the ship’s operators/owners have committed and in which they are directly involved.

- Every ship should have a Procedures Manual that states clearly what must be done on board the ship during normal operations and in emergencies;

- Every ship (and its systems) should be inspected (“audited”) by her company and also be the flag state to ensure that the ship and its operators/owners should be following the procedures given in the Manual;

- Every ship operator/owner should have a Designated Person Ashore who is the direct contact in emergencies and during normal operations to ensure that the ISM Code is being adhered to. ship to be maintained in conformity with the provisions of relevant rules and regulations and with any additional requirements which may be established by the Company.

International Ship and Port Security Code (ISPS) was introduced in 2004 in response to the terrorist attacks involving aircraft that, on 11 September 2001, were flown into the Twin Towers in New York, the Pentagon in Washington and that crashed in the US state of Pennsylvania. The terrorist suicide attack on the French tanker Limburg in the Gulf of Aden in October 2002 speeded up the introduction of this Code.

The Code was introduced to ensure that ships, containers and other items of cargo are not used to carry bombs or be used for terrorist activities. In terms of this code, every port should have good security systems that prevent potential terrorists from gaining access to either the port, cargoes or ships in port. Ships themselves also need to have good security systems to prevent illegal boarding of ships. At least 96 hours before arriving at a port, ships are also required to provide the port state control authority with a detailed crew list, the vessel’s cargo manifest, and a list of the vessel’s last ten ports of call.

Load line Convention governs the maximum permissible draught of ships and relates to the levels to which a ship may be loaded depending on the ship’s size, her classification (bulker, tanker, containership, etc.) and the area in which she is operating.

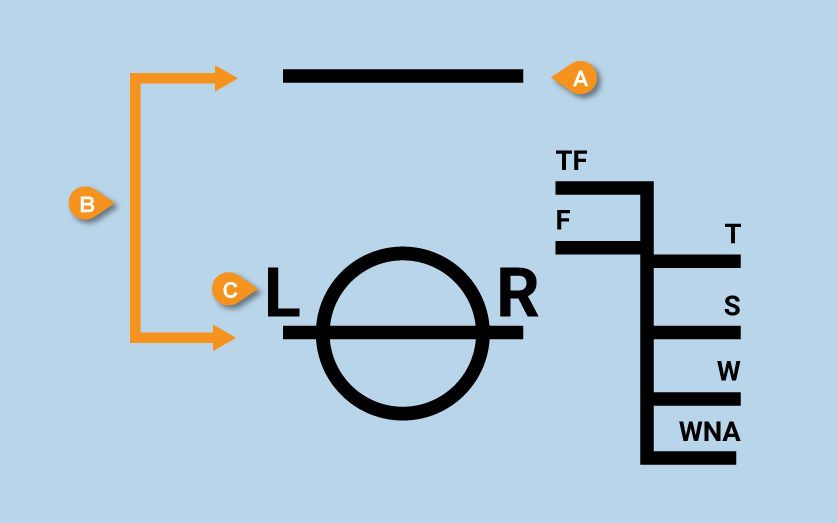

The loadline was the idea of a British politician Samuel Plimsoll who introduced a law in Britain whereby every ship had to have a special marking on both sides of the ship. Subsequent modifications of the loadline regulations included the formula that is used to position it at a prescribed measurement from the main deck. The loadline is now compulsory on all ships and was called the Plimsoll Line, but is generally referred to now as the loadline. (See the key below for the meaning of each black letter. The yellow lines and the letters in the yellow arrows are only labels for the diagram – see their meaning below.)

A Deck Line

B Summer freeboard (The measurement from the Summer mark S to the main deck of the ship.)

C These show the Classification Society (Lloyd’s Register) that “classes” the ship. Other ships may have the letters A B (American Bureau of Shipping) or N V (Det Norske Veritas) or the initials of other Classification Societies here. The black letters shown in this diagram indicate levels to which the ship may be loaded when operating in specified areas. These are internationally agreed areas that are fixed according to either water density or the general weather conditions in each area. Seasonal weather is also taken into account, especially in those areas where conditions experienced in summer are very different to those in winter or in a cyclone season.

TF Tropical Fresh : Tropical areas where the water is fresh (e.g. the Amazon River.)

F Fresh Water : Areas where the water is fresh (e.g. parts of the St Lawrence Seaway and the Great Lakes of North America.)

T Tropical Water : Any area inside the tropics (e.g. a ship going from Nigeria to the Caribbean Sea will pass through tropical water.)

S Summer : Summer zones are marked on a special map of the world according to the general weather conditions experienced. The entire South African coast is a designated Summer Zone, even during winter!

W Winter : Winter zones are marked on a special map of the world. These are zones where stormy conditions can occur at particular times of the year.

WNA Winter North Atlantic : The northern part of the North Atlantic Ocean in winter and in some areas of the Southern Ocean. These are areas where severe stormy conditions are experienced regularly.

Ballast Water Control Convention governs the need to control the discharge of ballast water in ships. All ships – even fully laden vessels – require some ballast water to ensure that the ship is trimmed properly and also to minimise the ship’s rolling. The ballast water is taken onboard in one port and is discharged in another. In this process, and despite grills on intake valves, marine organisms that are taken in can easily be transferred from one port to another.

For example, a ship that discharges an iron ore cargo in China will take in ballast water before sailing from the Chinese port. That ballast water will contain small (even microscopic) marine organisms that live in the water in the Chinese port. If that water is kept in the ballast tanks until the ship arrives in Saldanha Bay to load her next cargo of iron ore, as the ballast water is discharged in Saldanha Bay, those foreign organisms will be discharged with the water. This means that foreign (exotic) organisms are introduced to the water in Saldanha Bay, a most undesirable situation.

However, if the ballast water is released into the sea en route between the Chinese port and Saldanha Bay, and replaced with new ballast water, the new intake of ballast water will contain organisms more like the Saldanha Bay marine life, and therefore less harmful to the environment. Ballast water exchange while at sea may only be done when the ship is a minimum of 200 nautical miles from shore and in water with a minimum depth of 200 metres. To exchange ballast water, the ship can use the “flow-through” or sequential (tank-by-tank) method. At least 95 percent of the total ballast water should be exchanged between ports.

To kill exotic organisms in ballast water, chemicals can be put into the ballast tanks or mechanical and electronic measures can be put in place such as ultra-violet radiation, filtering of water, deoxygenation of the water or heating of ballast water.

The Ballast Water Control Convention requires all ships to have a Ballast Water Management Plan that includes the accurate recording of amounts of ballast water taken in and discharged.

Detention of Ships

Ships may be detained for a number of reasons, ranging from non-compliance with IMO regulations to debt.

Detention of Ships for non-compliance with IMO regulations

A Port State Control body (e.g. SAMSA) or a Flag State Control body (e.g. SAMSA) may detain a ship if the ship does not comply with IMO regulations and therefore she is technically unseaworthy. Examples of deficiencies that may cause the ship to be detained include the following :

- Life-saving equipment (e.g. lifeboats, liferafts) is inadequate;

- The ship is inadequately manned;

- Crewmembers are not properly qualified;

- The ship is in a poor condition;

- The accommodation is unhygienic;

- Mandatory certificates have not been updates;

- and many other deficiencies.

The Port State Control body or Flag State Control body will detain the ship until it is satisfied that the deficiency has been rectified, when permission wil be given for the ship to continue trading.

Detention of Ships for Debt or other Legal Reasons

A ship can be detained because of a debt owed. For example, a ship is repaired in Port X, but an amount of $750 000 is not paid by the owner to the ship repair company. The ship repair company will probably appoint a lawyer to recover the outstanding amount from the shipowner. If persistent efforts fail to result in payment, the lawyer will probably seek to have the ship detained until payment is made or until suitable arrangements have been made for payment or, if the debt remains unpaid, the ship can be sold to recover the amount owing,

The repair company’s lawyer may appoint a lawyer in the ship’s next port of call to act on behalf of the owner and make representation to a local court to for an order for the ship to be detained. If the court agrees, it will issue a detention order, prohibiting the ship to sail from that port until payment has been made, or until satisfactory arrangements have been made for payment, or until the shipowner can convince the court that payment was made and that the ship was detained in error.

In South Africa, the sheriff of the court serves a notice on the Master of the ship that the ship may not sail, and measures are put in place to prevent her from sailing (e.g. her documents are removed from the ship, and if ncessary, security officials are put aboard to prevent anyone from entering the wheelhouse.

In some countries, including South Africa, an associated ship (e.g. another ship belonging to the same company, or a ship that has some connection to the owner of the ship that incurred the debt) can be detained until the matter has been settled.

Role of Maritime Lawyers

Lawyers have a number of roles in the shipping industry. They will be asked to draw up or review contracts such as charter parties, bunkering agreements or contracts relating to stevedoring or crewing of ships.

Disputes often arise. These relate to matters such as a guarantee on new ship or equipment, damaged cargo, accidents, detention of ships, demurrage or dispatch claims, charter party issues, salvage or ocean towage, quality of fuel provided by bunker suppliers, bills of lading, and any other matter where one party believes that another party is to blame for a loss of any kind. If the matter cannot be settled by negotiation between the disputing parties, it can be referred to a court or to an arbitration process. In an arbitration process, an arbitrator – usually an experienced legal expert – is appointed by mutual agreement by the disputing parties. Often the arbitration process is governed by the original contract that may stipulate who the arbitrator will be or where arbitration will happen if it is needed. The arbitrator’s ruling is usually regarded as final.

To assist each party in a dispute, lawyers will be commissioned to provide advice and usually to act for the parties involved in the dispute.

In South Africa, a marine court of inquiry is usually established following an accident at sea, especially where loss of life or oil pollution has occurred. This inquiry is presided over by a judge or magistrate who usually sits with at least two assessors who are experienced seafarers or other experts in the maritime sector in which the accident occurred. Such a court will pass judgement on the allocation of blame for the accident, recommend steps to avoid similar accidents in the future, and recommend whether further action is needed against anyone involved in the accident. Each party involved in such an inquiry usually appoints a legal team to assist in the defence of its actions at the time of the accident, and to advise generally on the matter.

E Whale that was detained in Cape Town for two years because of a debt owed by her owner for marine engineering work done on an associated ship A Whale. Photograph : The Late Aad Norland