Anyone can become a ship owner – an individual, a company, a bank, a consortium of companies, or other group. Whoever owns a ship wants the ship to be an investment in terms of its ability to earn money by moving cargo, or by carrying passengers, or by providing a service (e.g. tugs or survey ships or oil rigs, etc.) Profits, of course, are important to the shipowner.

Ship Finance

A shipowner has significant financial burden as costs of buying and operating a ship can be very high.

Capital Costs (The cost of buying or building a ship)

Ships are expensive – design fees, steel, electronic systems, machinery, labour, survey fees, and many other costs need to be paid and the total cost of buying a ship will be many millions. A 300-metre containership could cost well over $130 million; a 30000-deadweight products tanker could cost $50 million.

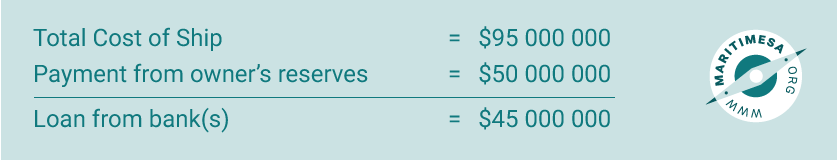

When buying or building a ship, the major problem for the shipowner is to find the money. Whatever the owner cannot provide himself, he will have to get a loan (also called a mortgage) from banks for the rest – and pay interest on that bank loan. A shipowner may want to “write the ship off” over 15 years which means that the ship is debt-free after 15 years.

For example :

If the owner wishes to write the ship off over 15 years, he will have to pay back at least $3 000 000 plus interest per year. Depending on the interest rate that will be charged, the interest that he has to pay each year could be around $4 million for the first few years. The amount of interest will reduce over the 15 years, but he will end up paying a lot more than the $45 million he owed the bank in the first place!

- Operating Costs – These are costs that the owner needs to pay to keep the ship operating. Those costs include

- Insurance cover for the ship (loss of or damage to the ship– hull and machinery insurance – see Grade 12 work) and for any liability that the ship may incur such as damage to cargo, damage to other ships or other objects, the cost of necessary diversions, injury to crew members or visitors to the ship – Protection & Indemnity cover – see Grade 12 work). Surcharges may be added if the ship is to pass through a pirate-infested area or close to a war zone.

- Maintenance of the ship and drydocking. These costs include ensuring that the ship is equipped with safety equipment and life-saving equipment, that the lifeboats and fie-fighting equipment are kept properly maintained – and that the ship is maintained according to the international regulations relating to seaworthiness and safety.

- Crew’s salaries

- Registration costs – These are payable to the authority in the country where the ship is registered. The costs of the classification society (see Grade 12 work) also have to be paid.

- Administration costs – These relate to the salaries and other costs surrounding the shore staff, the cost of the company’s offices, etc.

- Tax payable by the shipowner

- Stores and spares for the ship

- Depreciation on value of the ship. This includes the repayment of the loan but also should include making provision for the eventual replacement of the ship after 15 or 20 years.

- Fuel Costs – These are usually budgeted for separately. Fuel is often bought in bulk via a specialist bunkering company.

- Port Costs – These include

- Charges for tugs, pilotage, and berthing crews

- Time alongside in a port (also known as port dues)

- Light dues – In South Africa, these are payable on one call per six months and help to pay for the maintenance of navigational aids along the coast and in the approaches to the harbour.

- Use of shoreside cranes (if applicable)

- Canal/Waterway Fees – If the ship passes through a canal (e.g. Suez Canal, Panama Canal, etc) a transit tariff is charged.

- Sundry Costs – These include port agents’ fees, fees charged by local maritime authorities, stevedoring (usually recovered from the cargo owner).

Other Responsibilities of the Ship Owner

Besides the financing of the ship’s operation, an owner is also responsible for other important matters

- Cargo – The owner may find cargo himself, and in the case of liner companies such as Maersk Line or MSC, the company has a team of representatives whose job is to find cargo for the ships. Bulk carrier or tanker owners usually place their ships in the charter market where shipbrokers find cargoes – either one-off cargoes or regular cargoes such as moving coal between Richards Bay and China on a regular basis, or moving oil products along the South African coast – or along the European coast.

- Crewing The owner may wish to crew the ship himself, or he may engage a crewing agency to crew the entire ship or to find certain officers or crewmembers for the ship. Other issues regarding the crewing of ships include the following :

- Every ship has a minimum manning requirement (i.e. how many crew members have to be aboard; which ranks have to be aboard.)

- All crewmembers need to be qualified for their rank in terms of an international regulation called the Standards for Training and Certification of Watchkeepers. For example, a small ship that will trade only along the South African coast will have different requirements in terms of qualifications of her officers than a large containership trading between South Africa and Europe.

- Crewmembers are contracted as employees of the company or they are contracted via a crewing agency to serve on a specific ship, in a specific rank, at a specific salary and for a specific time.

- Countries such as Philippines, India, Croatia, Poland, and Ukraine supply thousands of seafarers to ships across the world.

- Traditional sources of seafarers (e.g. countries in western Europe) do not provide as many seafarers as they previously did. This is because more shoreside careers are available now; some people prefer the unemployment benefits ashore; western shipping companies were sold off, thus decreasing the sea-going opportunities for young people; western seafarers became too expensive when compared to those from Philippines, India, other Asian countries or eastern Europe who now dominate the world’s seafaring population.

- There are serious disadvantages of the process of contract crewing from elsewhere. These include :

- Different nationalities aboard a ship can cause language confusion and ineffective communication.

- During emergencies, loss of life or serious damage to the ship can occur due to differences in language

- Crew on contract are not as accountable for damage or lack of maintenance to the ship as “company-employed” crewmembers. (A contracted seafarer may not return to ships of that company again and therefore may not display the same loyalty as a “company-employed” person.

The Teekay Corporation employs all its sea-going personnel, creating a stable supply of seafarers. Photograph : Teekay

- Legal Matters – Because shipping is an international business and has to operate according to international laws and regulations, most large shipping companies have an in-house legal department. Smaller companies may engage outside maritime legal experts to act on their behalf. The legal team would handle a number of issues relating to the operation of the company. Examples include the following

- registration of the company’s ships,

- ensure the ships’ insurance cover is appropriate

- provide updates on changes to legal requirements for ships

- check any legal documents that the company needs to sign e.g. charter parties, agreements or contract with crewing agencies, ship managers, bunker suppliers or ship chandlers, etc.

- handle any insurance claims against the company for cargo damage,

- other matters where legal claims could arise or where the correct legal processes need to be followed.