[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://vimeo.com/522358814″][vc_column_text]When ships come into harbour, or leave a harbour, they require assistance to manouevre in the restricted harbour area. Therefore, harbour tugs have developed over the years to help ships turn, to push them carefully against a wharf when berthing, or to tow them away from that wharf when the ships are ready to leave the harbour.

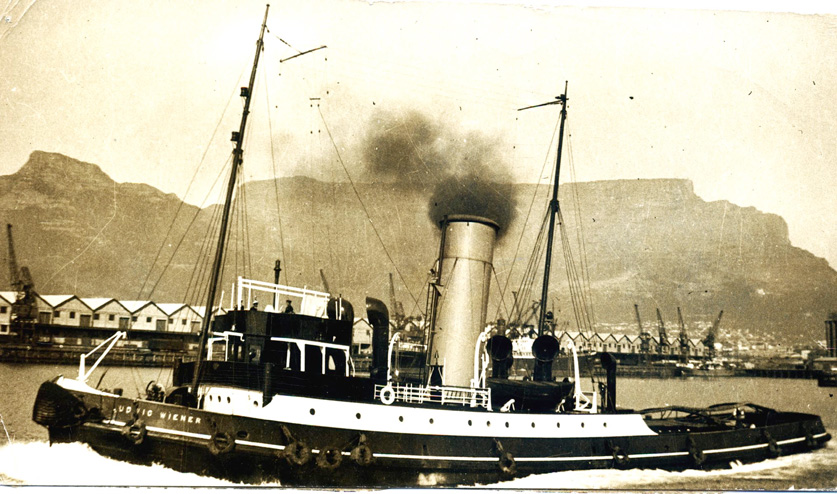

In South Africa, the first really large powerful tug was commissioned in 1913 to operate in Cape Town. She was Ludwig Wiener (photograph below), and had twin coal-fired steam engines that could develop 2400 horsepower.

Like most tugs of her time – and the general arrangement was been continued over time – Ludwig Wiener had a long towing deck down aft, powerful engines, and twin screws. She had two roles : that of a harbour tug to assist ships in and out of harbour, and the role of a salvage tug to attend ships in distress or to undertake ocean towage contracts when required. Note the buffer on the bow that enabled her to push ships, while tyres on her sides were used as fenders for her harbour operations. She was transferred to Durban in 1941 and operated until she was scrapped in 1961.

Seen here helping to berth a liner on the UK-South Africa-Australia trade, T.S. McEwen was the world’s most powerful tug when she was delivered to the South African Railways & Harbours in 1925. She undertook several ocean towage and salvage operations until she was withdrawn from service in 1971. Note the long after deck, a characteristic of all those steam harbour tugs as it was useful for towing operations.

The East London tug E.S. Steytler, one of nine similar tugs built in the 1930s for service in South African harbours and to undertake ocean salvage and towage operations. They were all coal-fired. E.S. Steytler is seen here without her bow fender and her tyre fenders have been raised as this photograph was taken when she was preparing to tow a dredger from Durban to East London. Another two similar coal-burning tugs were built in the 1950s. By the mid-1980s, all these steam tugs had been withdrawn from service in favour of multi-directional tugs. (See below)

A new class of harbour tug came out in 1951 – the oil-burning F.T. Bates in Cape Town (above) and her sistership A.M. Campbell in Durban. The fact that they were oil-burning gave them a longer range for ocean towage and salvage operations and also made them easier to manouevre when doing harbour work. They still had the long after deck, but like the earlier tugs, they were not really suited to operations in heavy seas. Two upgraded and more powerful tugs – Danie Hugo and F.C. Sturrock – entered service in 1959, and a third, slightly modified J.R. More, arrived in Durban in 1961. She was the last steam tug built for service in South African harbours. She is shown below turning the British India Line vessel Kenya in Durban harbour.

The tugs with conventional propulsion systems were difficult to manoeuvre, although experienced tug masters overcame the difficulties and provided an excellent service, even in unfavourable weather.

A new development was the design of multi-directional harbour tugs whose propulsion system allows them to change direction immediately the tugmaster required. This helps to manoeuvre ships in strong wind and in small areas. One of the first of this class of tug in South African ports was the Durban-built W. Marshall Clark (above).

The system used in most South African harbour tugs is the Voith-Schneider propulsion system. Apart from two tugs operating in Saldanha Bay, all the multi-directional tugs in South African harbours were built in Durban.

Imonti (top) and Shiraz in Port Elizabeth. Built in Japan, Imonti has a Z-peller system, while the Durban-built Shiraz has a Voith-Schneider propulsion system.

To replace older tugs and to provide tugs for Ngqura, a new series of tugs is being built in Durban. Mkhuze (below) was one of the first of the new tugs built for the tug-replacement programme.

This ship is being turned by two multi-directional tugs. The forward tug is pulling the ship’s bow round to starboard while the after tug is pulling the vessel’s stern to port.

Other Harbour Craft

To take the pilot out to incoming ships and to take the pilot off out-going vessels, small tugs were used. These were coal-fired steam tugs and although they served the purpose, they were relatively difficult to handle in rough weather.

Used originally to tow lighters to and from ships anchored off Port Elizabeth, James Searle (above) became a pilot tug in both Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. She was scrapped in 1950.

In this photograph (taken in about 1975), the pilot tug Cecil G White has just embarked the pilot from the bulk carrier Johan Hugo as she sails form Cape Town. The pilot tug was one of five Italian-built vessels that replaced the older pilot tugs in South African ports in the late 1950s. Besides taking the pilots to incoming ships or taking them off departing ships, the pilot tugs were used to handle small vessels in the harbour.

When the time came to replace the pilot tugs, a Cape Town shipyard won the contract to build the first pair of steel pilot launches, one of which was A.C. Craigie (above). Further launches were built in Cape Town – see the photograph of PB Gannet below.

Yet another series of pilot launches has been built in Durban.

Small tugs are also included in the fleet of harbour craft at each port. Blue Jay (below) is an example of these vessels that serve as pilot tenders and as tugs to assist smaller ships in and out of harbour.

Tugs used for Salvage and Ocean Towage Operations

When ships have broken down, or are on fire, or have gone ashore, or are in any other danger following a collision or structural damage, a tug may be called to tow the disabled ship to port, to assist with fire-fighting operations, to try to refloat the grounded ship, or to provide other assistance.

Originally, the South African harbour tugs were designed to undertake harbour work as well as ocean towage and salvage operations. The tugs were not ideal for either role as for their major role – harbour operations – they had a rounded bow, low fo’c’sle and heavy timber beading along the sides. When they did go to sea for salvage work, they were not good in heavy seas. Despite this, they performed some remarkable salvage and towing operations, largely owing to the seamanship skills and long experience of the tugmaster and his crew.

The picture above, taken in March 1948, shows Cape Town harbour tugs towing the freighter City of Lincoln that had been refloated after running aground on Quoin Point (west of Cape Agulhas) four months earlier. This was the one of the most significant salvage operation undertaken by the old steam harbour tugs.

Large companies had developed to undertake both salvage and ocean towing operations for which special tugs were designed. Ierse Zee (above) was one such tug that was operated by the large Dutch company Smit. This photograph was taken in 1963 after she and another Smit tug, Tasman Zee, had towed a tanker from South America to be drydocked in the Sturrock Drydock in Cape Town for a replacement propeller to be fitted. Like all specially-designed ocean-going tugs, she has a raised fo’c’sle and a flared bow that made her better suited to operations in heavy seas.

A Turning Point for South African Salvage Operations

In 1971, the tanker Wafra ran aground at Cape Agulhas and began to leak thousands of tons of crude oil into the sea. Attempts by a small tug to refloat Wafra were unsuccessful, and the world’s most powerful tug at the time, Oceanic (below), happened to be passing the Cape at the time. She managed to pull Wafra from the reef, and on instructions from the South African government, she towed the tanker far south of the country where the South African Air Force sank the badly damaged vessel.

This was shortly after the world’s first major oil pollution incident when the tanker Torrey Canyon was wrecked on an island south-west of Britain and had caused extensive oil pollution. The South African government, with shipowner Safmarine, built two 26000-horsepower tugs to prevent a similar incident off the coast. The tugs were on standby along the coast to put to sea immediately a problem arose.

Although only one tug is now on permanent standby, the “emergency standby towing vessel” idea – developed by South Africans- is still in operation and has saved many ships (and lives) from imminent danger over the years.

The South African emergency standby towing vessel idea , is now used by a number of other countries.

[new_royalslider id=”13″]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]