One can stop a vessel by one of the following methods:

- Inertia stop. Stopping the engine(s) and coasting to a standstill with the friction of sea and air overcoming the ship’s inertia. The total distance run will depend on the type of vessel, the initial speed, the displacement, the trim and condition of the underwater plating and other factors. For warships the distance in miles may be only one tenth the initial speed in knots, but for fully laden tankers it could be more than half the speed.

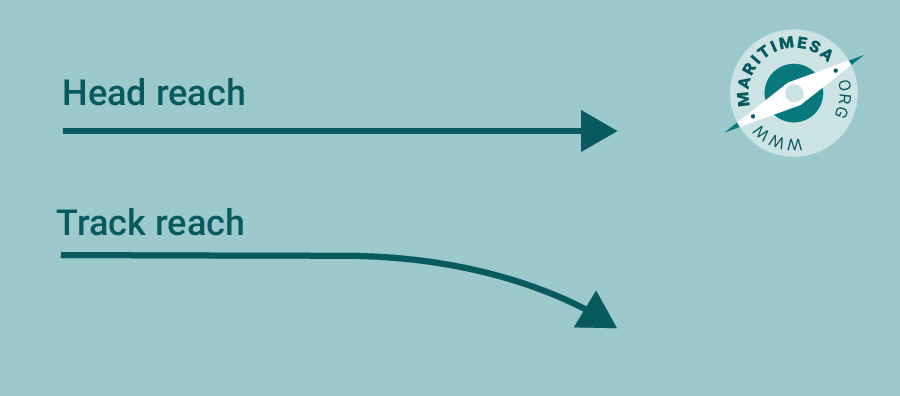

- Crash stop. A crash stop is when the engines are put astern to stop the ship as rapidly as possible. The total distance travelled along the ship’s actual path is known as the track reach and the total distance travelled in the direction of the initial course is called the head reach.

The factors affecting the distance travelled are the same as those for the inertia stop as well as the type of machinery and the use of the rudder. A diesel engine ship usually takes approximately 2 minutes after stopping the engine(s) until it starts going astern. In a ship having a single, right handed propeller, the stern will also swing to port when the engines are put astern. The track reach is measured in ship lengths. A fully laden tanker could take up to fifteen lengths to stop. A 200 000 ton fully laden tanker will take approximately 25 minutes to stop from 16 knots. - Use of the rudder. The rudder can also be used to provide additional retarding effect when stopping in an emergency. If the engines are put astern immediately after stopping them, the rudders soon become ineffective. During various ships’ trials it was found that by reducing the revolutions in steps and using the rudder hard over each time with a final full astern and the wheel again hard over , it effectively reduced the ship’s head reach more than if the engines had been put astern and the rudder kept amidships. However, the above would depend on the time and distance available to stop. If a sudden stop is necessary, it will be best to stop the ship by going full astern as soon as possible. The engines should be put astern after a delay of not more than three minutes.

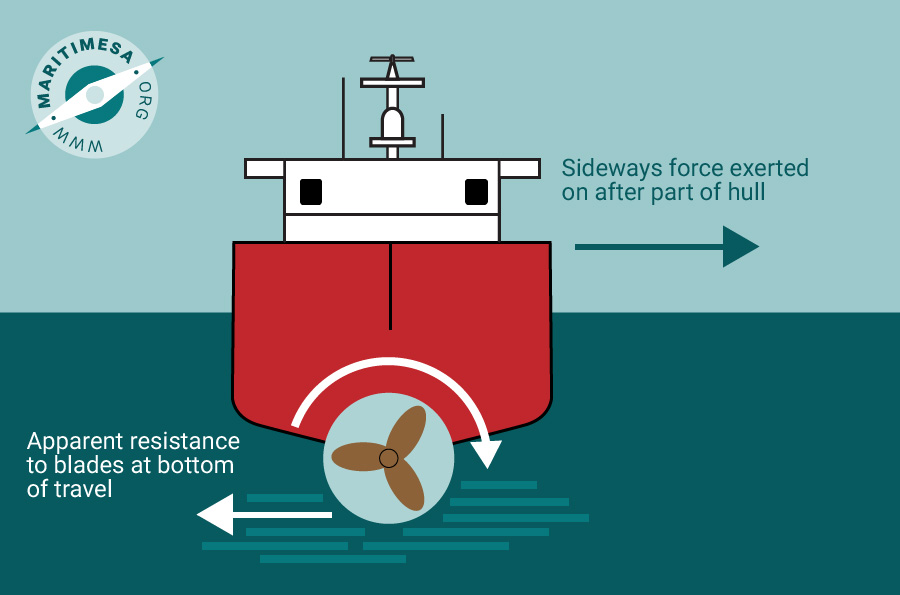

- Astern affect. As stated previously, a single screw ship going astern will tend to swing her stern to port because of the transverse effect of the motion of the propeller (paddlewheel effect). In addition to this, when the ship starts moving astern, the pivot point of the ship will move from its normal position, one third of the ship’s length from the bow, to a position well aft. Since the wash from the propellers will be in the opposite direction to the rudders, it will have no effect on them. The total effect of going astern will adversely affect the steering and the ship will steer with great difficulty.

Paddle wheel effect.

- Anchoring in an emergency. It is standard practice before coming into harbour or when the ship is manoeuvring in confined waters, to prepare the anchor(s) for letting go should an emergency arise. Power is put on the forecastle machinery and the windlass is turned over out of gear. The windlass is then put into gear and the anchor(s) are “walked back” to loosen them in the hawse pipes. The brake of the windlass is then applied. Should it be necessary to drop anchor in an emergency, the brake is released and the anchor will drop. Once the anchor is on the bottom the brake is applied in a controlled manner to control the cable run-out and slow the ship down. If the brake is applied sharply, the anchor will merely drag along the bottom.